Galaxy Research Summary

Choose The Basics

(rated G for general audiences) ...or...

The Details (for the cognoscente)

How do galaxies evolve, and why do they look the way we see them today?

On our own

Local Group of Galaxies there are a wide variety

of galaxies, each composed of 1 to 100 billion stars.

There are...

|

... large spiral galaxies, like the Andromeda Galaxy, M31, our nearest

large neighbor...

|

|

...roundish, fuzzy, and rather small elliptical like galaxies...

|

|

|

...and irregularly-shaped dwarf galaxies with bright regions

of young, massive stars just recently formed in the last few million

years.

|

In a nutshell, galaxies begin as clouds of hydrogen and helium gas

which are turned into stars as the galaxy "ages". Stars generate

energy by the nuclear fusion process, transforming hydrogen and helium

into heavier elements like carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and even iron.

When most stars exhaust their supply of nuclear fuel, they undergo

spectacular and violent phenomena we call nova or supernova explosions,

or planetary nebulae ejections. By these processes, stars return most

of their material, including the newly-synthesized heavy elements

essential for life as we know it, back into interstellar space

whereupon the whole process begins again.

As an observational astronomer, I study the stars and gas in galaxies

to understand the interplay between stars and gas that shape the

appearance of a galaxy. Facilities I've used include

optical and infra-red observatories at...

Using radio telescope facilities at...

...I have conducted studies of the atomic hydrogen and molecular

(carbon monoxide) gas in galaxies. Such observations show that

often collisions and interactions between galaxies trigger star

formation bursts and drastically alter their appearance.

Some observations cannot be made

from the surface of the earth and require orbiting satellite

observatories. The Hubble Space

Telescope has been crucial

for making observations in ultraviolet light that are not possible from

ground-based telescopes. My collaborators and I use

the orbitting Chandra X-Ray Observatory

to conduct X-ray observations of hot,

million degree gas heated by supernova explosions and galaxy

collisions. We also use the Spitzer Space Telescope.

Understanding the evolution of galaxies requires ...

|

a detailed knowledge of individual galaxies in the nearby universe

such as our near neighbor, the dwarf galaxy

named the Small Magellanic Cloud located just 150,000 light years

from the Milky Way...

|

|

...and an investigation of

galaxies at the edge of the observable universe which we

see as they were billions of years ago when galaxies

first began to form.

|

|

Using a variety of observational techniques, I am seeking to

understand the physical processes that transform objects in the distant

universe into the galaxies all around us. My research program involves

understanding the chemical composition of stars and gas in

galaxies, the physics of star formation, and the dynamics of

stars and gas as galaxies are assembled and torn apart.

Students of all levels work with me on astronomical research projects at

telescopes here and around the world.

At WIRO

At Red Buttes

At Kitt Peak

The Evolution of Star-Forming Galaxies:

A Research Program in Star Formation and Galaxy Evolution

Understanding the origin of galaxies in the early universe and their

evolution to the present time is one of the fundamental astrophysical

challenges of this decade. A dominant paradigm is still emerging. Are

large galaxies built primarily by accretion of smaller proto-galaxies?

Was there a specific epoch when most galaxies formed? Are internal

(star formation) or external (cluster and environment) forces the

dominant influences on a galaxy's evolution? What are the conditions

and triggers that drive star formation?

My research programs are designed to answer these questions by

integrating our knowledge of the dynamical and chemical properties of

nearby star-forming regions with those in the distant universe. I

focus on three main areas relating to these origins themes. 1)

Galaxy kinematics and chemistry in the distant universe, 2)

the impact of star formation on the ISM of galaxies, and 3)

the formation of massive stars and star clusters. They make use

of the ultraviolet capabilities of the HST + STIS/Cosmic Origins

Spectrograph, the X-ray spectroscopic capabilities of Chandra/XMM, and

the new generation of instrumentation on large ground-based telescopes

like Gemini which I am eager to help develop so that this science may

proceed.

One fruitful approach to understanding how galaxies evolve is through

the study of the fundamental galaxy scaling relations: correlations

between luminosity, size, mass (as traced by velocity width), and

metallicity. The advent of 6-10 m class telescopes and infrared

spectrographs make chemical and kinematic analysis at high redshift a

potent way to probe the evolution of the universe

(

Kobulnicky, Kennicutt, & Pizagno 1998 ,

Kobulnicky & Phillips 2004

).

In order to connect the

chemical properties in the early universe inferred from QSO absorption

line studies with the chemical enrichment scenarios envisioned for

local galaxies, I have initiated a program using the Keck telescopes

with multi-object optical and infrared spectrographs to directly

measure the chemical properties of star-forming galaxies at high

redshifts using emission lines from H II regions. Some initial results

at intermediate redshifts (z=0.4) show that chemical enrichment is

strongly correlated with a galaxy's optical luminosity and mass, and

that chemical abundance ratios can constrain the future evolutionary

path of star-forming systems observed at earlier epochs (

Kobulnicky & Zaritsky 1999 ).

More extensive studies of hundreds of galaxies over the redshift range

z=0.2 - 1.0 show that galaxies at 10 Gyr lookback times are

significantly brighter and less chemically enriched compared to local galaxies

of comparable mass and luminosity (

Kobulnicky et al. 2003;

Kobulnicky & Kewley 2004 )

At higher redshifts near z=0.8 to z~3,

there appears to be significant evolution of fundamental galaxy scaling

relations

( Kobulnicky & Koo 2001),

but so far only a few of the most luminous

objects have been studied. In the next few years, I plan to be

developing and using the capabilities of multi-object optical and

infrared spectrographs on ground-based telescopes like Gemini to

measure the chemical content and spatially-resolved kinematics of

distant galaxies. These kinds of observations constitute the best

tests of numerical and semi-analytic models of galaxy and structure

formation in the early universe.

|

In the local universe, galaxy interactions and starburst-driven winds

are often invoked as feedback mechanisms for regulating star formation

rates, removing gas from galaxies, transforming one type of galaxy into

another, or expelling metal rich gas from galaxies with shallow

potential wells. These same mechanisms must play an even larger role in

driving the evolution of galaxies in the early universe, yet, their

impact in well-studied nearby galaxies is not yet clear. Local

starforming galaxies are chemically homogeneous on scales of <2 kpc (

Kobulnicky & Skillman 1996,

1997 ) despite the presence of concentrated starbursts which should

give rise to large localized chemical enhancements

(Kobulnicky et al. 1997 ). Starburst-driven winds drive

freshly-synthesized heavy elements on a long (100 Myr) excursion into

galactic halos before they are mixed back into the ISM and participate

in subsequent generations of star formation. How effective is the

feedback phenomenon that regulates the star formation rate in galaxies

and shapes their evolutionary paths?

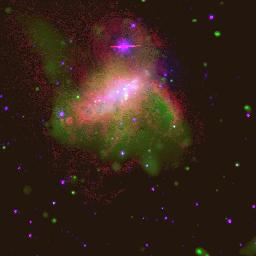

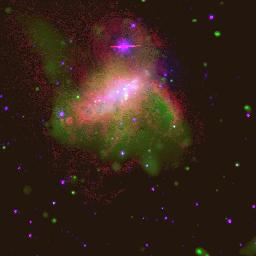

In some galaxies we see clear evidence of freshly-produced heavy elements synthesized in

the current burst of star formation being expelled from galaxies

in a hot 1-million K phase

(Martin, Kobulnicky, & Heckman 2002) . This work was featured

in a Chandra X-Ray Observatory Press release

and by Astronomy Picture of the Day

My collaborators and I have also begun a campaign of HST/Cosmic

Origins Spectrograph observations and FUSE archival data of local

galaxies to probe the chemical content and ionization properties of gas

in the halos of nearby galaxies.

|

|

Local galaxies with high star formation rates are often the products of

galaxy mergers. Tell-tale tidal tails are often seen in the neutral

hydrogen gas kinematics (

Kobulnicky & Skillman 1995 ) or in the

molecular gas dynamics. A galaxy's position

within a cluster may have a strong influence on its interaction

history, and on its ability to retain interstellar material.

The gas content of galaxies at higher redshifts is

particularly important since the amount of raw material for star

formation which remains determines the future evolutionary

path. We are engaged in a program to measure the neutral

hydrogen content of compact star-forming galaxies at $z$=0.05--0.2

to determine if they may be the progenitors to todays spheroidal

galaxies

(Kobulnicky & Gebhardt 2000 )

and (Pisano, Kobulnicky et al. 2001).

Using Hubble Space Telescope archive data and Keck telescope

spectroscopy, I am surveying the gaseous and chemical properties of

cluster galaxies over a range of redshift and cluster environments to

understand the impact of environment on galaxy evolution. Two sample

galaxies with the highest N/O ratios, NGC 5253 and II Zw 40, appear to

be among the youngest starbursts known, judging from the flat, thermal

nature of the radio continuum. Making use of new VLA high resolution

continuum imaging, and data from the VLA archives, I have been working

to reconstruct the burst history of the proto-typical Wolf-Rayet

galaxy, Henize 2-10 and determine the nature of its compact radio and

ultraviolet knots (

Kobulnicky et al. 1995 ).

The small-scale and thermodynamic structure in the

interstellar medium of the Milky Way and Magellanic Clouds provide

important clues for understanding the energy balance in galaxies at all

cosmic epochs. I conducted some of the first millimeter-wave molecular

absorption observations against extragalactic background sources

(

Kobulnicky, Dickey & Akeson 1995 ) through the plane of the Galaxy,

revealing remarkably similar structures on lines of sight that probe

scales from 1 pc to 1 AU! These data show no evidence for extremely

cold molecular gas at large galactocentric radii claimed by some

researchers, but they do show that the molecular gas seen in absorption

in the Cygnus rift is rotationally very cold (8 K). The Magellanic

Clouds also show cold gas condensations even in the tenuous Bridge

region, providing evidence that star formation may take place in a wide

range of environments (

Kobulnicky & Dickey 1999 ). A more extensive HI

and OH survey of the Galactic Plane and the Magellanic Bridge region is

underway.

Back to Chip's Homepage